From The QT: A story to stick with...

In June 2024, writer Michael Chaplin examined the contents of his porch and told the intriguing tales of the walking sticks that have led him down the highway of life...

Recently watching Mammals, the latest of David Attenborough’s remarkable films about the animal kingdom, I watched entranced as a gorilla used the branch of a tree to help him walk along a path through dense jungle. Then he went and spoiled the touching image by braying a rival over the head with it.

This made me think about the history of the humble walking stick, which may be just as old as humankind itself. For a very long time it’s been used either as a weapon, not solely by gorillas; or symbol of authority, from Moses parting the Red Sea with one to Black Rod hammering three times with another on the doors of the House Commons to summon MP’s to hear the King’s Speech in the Lords. Then there’s that symbol of military authority, covered in leather with metal tips at both ends, the aptly named swagger stick.

It’s said men began carrying sticks when they gave up wearing swords. Now they seem more popular than ever, evidenced by the number of websites selling them in sundry guises, some at astronomical prices.

For those interested in seeing the real thing, there’s always the ancient emporium of James Smith & Son at 53 New Oxford Street, though it might be wise to leave your debit card at home. The collector of walking sticks even has its own technical term: rabologist.

As for me, I never actually set out to collect walking sticks. They just turned up: gifts from family, friends and work colleagues, a few inherited from the dear departed, plus one or two we picked up along the way. They all have a story attached to them, so here they are, with thanks to my friend Joe The Joiner and his cabinet-maker pal who’ve tried to identify the wood used on these sundry objects.

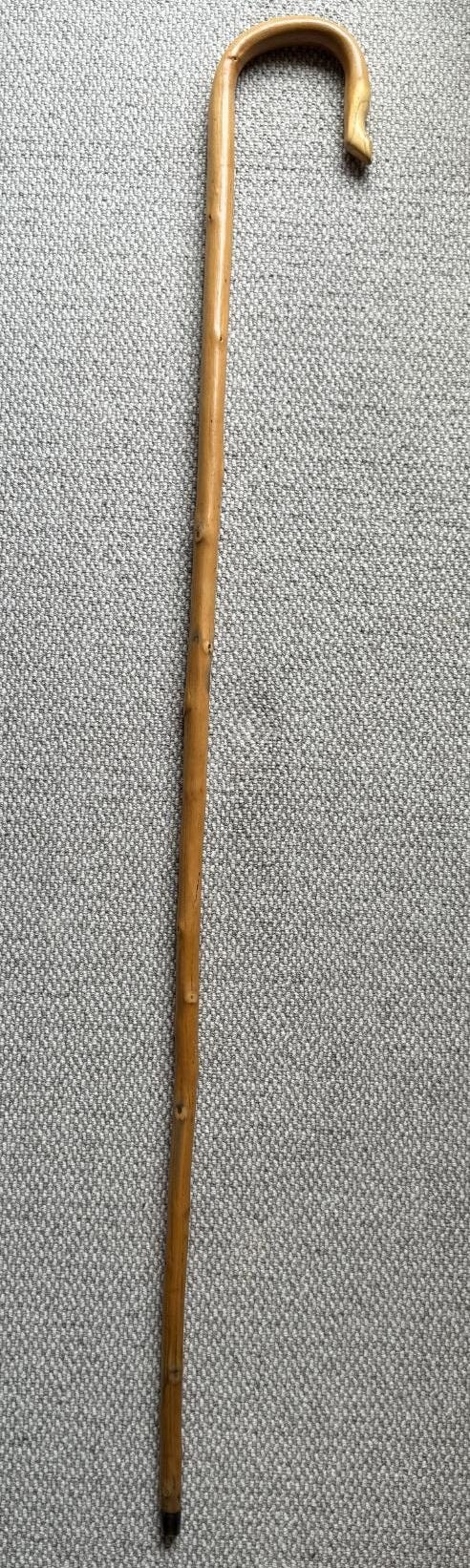

This substantial stick, or more properly ‘crook’, possibly made of willow, was given to me when I left my job as head of programmes for BBC Wales in Cardiff in 1994 to become a full-time writer. It was a gift from the staff of the new documentaries department which I’d helped set up.

During its presentation at my leaving-do there was a ponderous reference to how I had ‘shepherded’ the unit into life. As the item stands some five feet high, I’ve never actually taken it on a walk.

Apart from anything else, I don’t have the hair to pass myself off as an Old Testament prophet. But I’m glad to have the crook as it reminds me of a happy period of my life — and the beginning of a leap into the unknown that could have ended in tears but somehow didn’t.

The smaller companion of the above. About 10 years ago I returned to Crete many years after visiting it as a schoolboy. We stayed in an apartment near Chania, walked, swam, haunted museums, including the great ruins of Knossos, ate nice food and drank rough wine.

Every night on returning to base we saw a group of local people — three women and a solitary man — sitting on kitchen chairs nearby. The elderly man worked as he socialised, stripping the bark from a long stick. To begin with, we shared smiles and greetings that became warmer as the week went by.

One day we visited the immaculate Allied war cemetery at Souda Bay, where 2000 Commonwealth soldiers were buried after the Nazi invasion of May 1942. It was an achingly beautiful place by the Mediterranean, deserted apart from us and a young man dressed in the uniform of the New Zealand Navy, his face decorated with striking Mauri tattoos. He searched for the graves of his countrymen, stood silently before them, before giving an impeccable salute.

Our thoughts were also of home. Not far offshore, the Hebburn-built Royal Navy destroyer HMS Kelly, was attacked and sunk by Stuka dive-bombers as it tried to evacuate Commonwealth troops with the loss of 131 men, many from the Tyne.

That evening we returned for the last time to our flat before we flew home, receiving the usual warm greeting from our Cretan neighbours. Before we left the old man stood up, murmured a few words in Greek and held out the stick he had now finished.

We didn’t understand what exactly he said, but we understood it was a gift, somehow connected to the Commonwealth soldiers and seamen who never left Crete to return home.

The women nodded, we murmured our thanks and turned away with our gift: a tall stick made of Mediterranean soft wood, one end fashioned with slow heat into a circular handle, tied with wire. Before we parted from our holiday friends, Susan took a photo of maker and recipient to capture the moment, which has lived with me ever since, especially the old man’s sad expression.

This hefty beast of a stick was also the product of a foreign trip, this time to South Africa. We were part of a group touring the country to build cultural ties between our North East and the Eastern Cape.

One night we arrived late in its capital of Port Elizabeth, checking into a hotel on the beach. I was woken a few hours later by the blazing light of the rising sun, went to the curtain and looked out over the Indian Ocean. In front of me a cargo ship nosed through the piers of the harbour. I instantly thought of my brother Chris, who in the early 60s was an engineer on various vessels of the Ellerman Lines, one of the great names of the largely extinct British merchant marine.

I still have a memento of one of his trips to South Africa, a short spear or assegai which he gave to me on returning home, much to my mother’s disapproval. I was only allowed to keep it on condition I never ever used it as a weapon…

A few days later I saw this two-tone stick in a market and bought it for Chris, who was a keen walker. It’s a brute of a thing, with its knobbled end more of a club, but Chris was pleased to have it and it only came back to me when he sadly confessed his walking days were over.

I was amazed when Joe told me the stick is made of lignum vitae (wood of life), which is famous for its extraordinary combination of strength, toughness and density. How it got to South Africa when it’s native to the Caribbean and South America (where it’s known as guayacan) is a mystery. Maybe it made the journey the same way as Chris: sailing across the Atlantic…

This singular object also came down through the family. The shaft is made of hawthorn, the handle of holly — meaning the stick was likely made in the UK — incorporating a striking carving of an alligator. Judging by the number of websites selling them, these objects are very popular, especially in the United States.

It’s so tactile to hold in your hand, with the tail curling around your thumb and forefinger and the creature’s jaw pressed into the palm of the hand. In fact, it’s the kind of thing that’s long been known as ‘a conversation piece’, an unusual object that gets people talking, perhaps especially by men who are keen to get to know an attractive young woman, the kind of encounter that appears in the novels of Henry James, if not on Newcastle’s Quayside on a Saturday night.

These two sticks are strikingly similar, almost identical: the shafts made of ‘hedgerow wood’ and the handles of two different kinds of animal horn. As walking sticks go, they’re rather mundane, but elevated for me by two things: they were made by brother Chris and used by our mother as she advanced through her 80s and into the 90s, her sight diminishing with every passing year.

Eventually it became so bad her children realised it wasn’t safe for her to stay in the home she’d made and immaculately kept for more than 50 years and needed full-time care. This broke her heart — ours too — but it had to be done. The sticks went with her, but alas, as things turned out, she didn’t use them for very long…

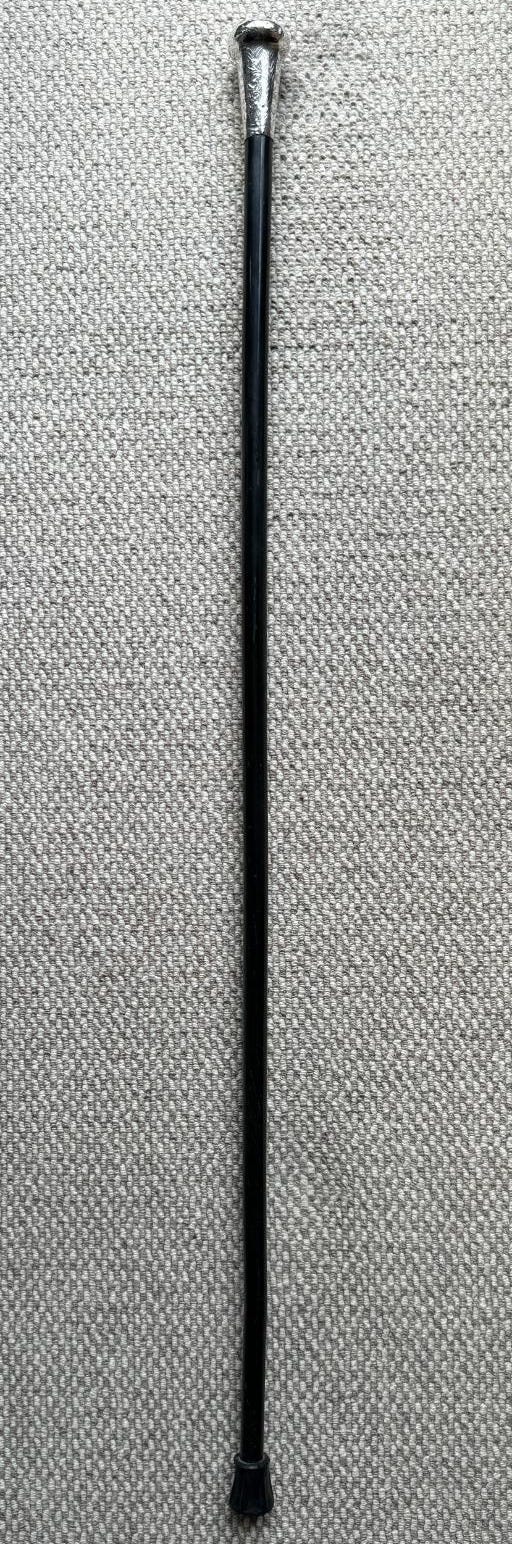

This fine thing — an ebony stick with chased silver knob — is something of a family heirloom, but of uncertain provenance. It seems likely it might once have nestled in the white-gloved hand of a dashing young blade in late Victorian or Edwardian times, just off to a ball perhaps.

In fact it makes me think of the film My Fair Lady — and Rex Harrison teaching Audrey Harrison how to be a lady, falling in love with her in the process.

The reality is more prosaic. Once upon a time my great-grandfather Rutherford played the role of butler in various grand houses in Scotland and Northumberland in late Victorian times and may have been given the stick by a grateful master — or indeed mistress.

It’s a beautiful, rather enigmatic thing. I love it, yet I’m unlikely to go out on the town with it. Not sure I could quite carry it off.

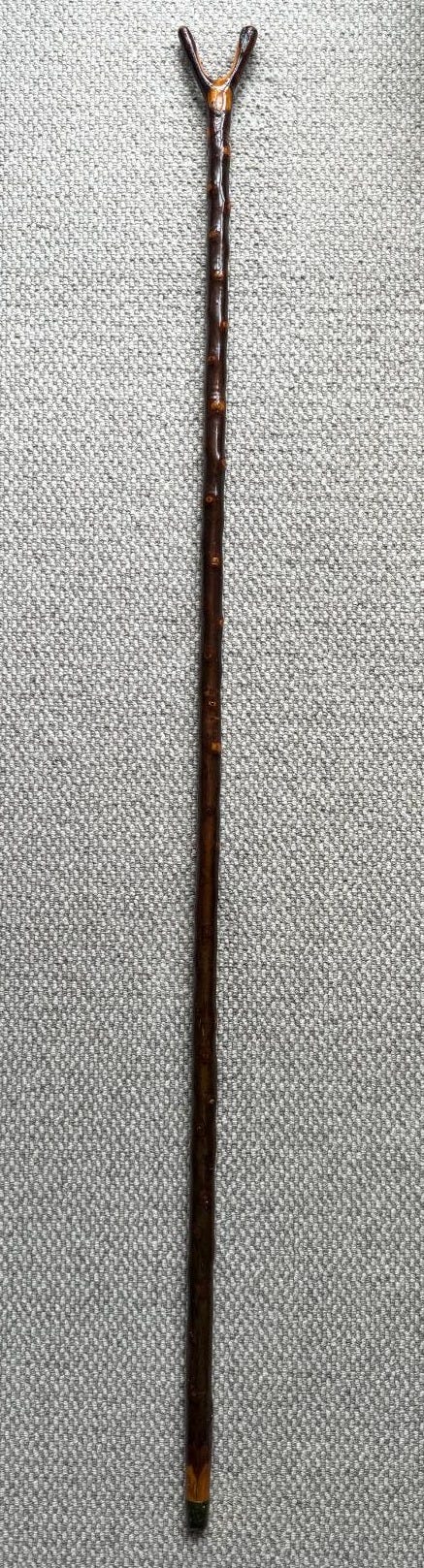

I’m very fond of this object, a pleasing chest-high blackthorn stick with a fork at the top where the walker can satisfyingly place a forward-facing thumb.

It’s a very nice thing, made for me by a very nice man. His name was Joe Chaplin, my Dad’s younger brother, and like Sid a pitman in the Durham coalfield. Also like my father, Uncle Joe suffered from heart disease later in life, although it never inhibited his lust for that life, exhibited in various enthusiasms.

As a young man he and his lovely wife Olive would cycle their tandem bicycle up hill and down dale, often in company with my Auntie Kathy and Uncle Walter. In later years they often took me and their sons Brian and Nick on epic outings from Ferryhill to Scarborough in their tiny Ford Popular.

In time Joe became a very enthusiastic bandsman, playing the B Flat bass tuba, and it’s him I will always thank for giving me one of the stand-out musical experiences of my life: listening to the Durham Mechanics Band playing Aaron Copland’s Anthem For the Common Man at the Memorial Service for my Dad in Durham Cathedral in 1986.

Later he led Mainsforth Colliery Band to victories in sundry contests, encouraging female players to join before retiring at the age of 70. He was in the best sense a jovial man, most evident in the story of what happened after the band finished playing one summer at the Durham Big Meeting and marched from the racecourse, still playing, on the way home. Their route took them past the front gates of Durham Gaol, at which point the band abruptly abandoned their marching tune and played something more fitting: Elmer Bernstein’s epic theme for the war movie The Great Escape.

Legend has it that there was immediate cheering from within the high stone walls, then the inmates started singing along with the tune. No prizes for guessing who was behind the wheeze…

Looking around for something else to do with his life, Joe met a walking-stick maker at St John’s Chapel Show in Weardale and caught the bug. He bought the gear he needed and set out to follow his dream.

‘It became a bit of an obsession with him,’ calls Cousin Brian down the phone from Spennymoor. ‘He and our Uncle Jack used to search Doggy Wood near Ferryhill for the hazel he needed. Then he’d go into the garden shed and lock the door behind him so he could work in peace.’

The only problem arose when Joe acquired some rams’ horns to fashion into rustic handles.

‘To make them pliable, bend them into the right shape, he boiled them for ages on the cooker, which of course stank the house out. There was hell on!’

Diplomatic relations were restored when Olive bought a portable stove so her husband could work in peace in his precious garden shed with Radio 2 blaring.

In time the hard work paid off. One year Joe returned to St John’s Chapel Show where his stick-making career began — and won first prize. ‘Then blow me he won it again the following year! It made him so happy, gave him a purpose,’ my cousin reflects. ‘Mind, he never entered Wolsingham Show, he reckoned the competition was too hot!’

As I say cheerio to Brian — ‘Ta-ra our Michael!’, he bellows — I resolve to make a pilgrimage to the next St John’s Chapel Show.

The sun will shine all day. The tea will be delicious. And Uncle Joe’s beautiful stick will be much admired…

This is the last of my accidently formed collection of walking sticks. It’s arguably the most ornate, certainly the most intriguing. Made of oak, its shaft is encircled by what seems to be a shamrock plant and what’s certainly a writhing snake with a goblet in its mouth. There’s also a finely rendered harp, which seems to confirm the notion the stick was made in Ireland. Then again maybe not…

The top of the shaft also features the stick’s most surprising feature: a rudimentary spirit level with its own tiny wooden ball. And it still works. Perhaps this lovely thing was made for a practical man, an engineer perhaps? That’s certainly the story that comes with it.

In 1975 along the route of the Stockton and Darlington Railway there were celebrations of its 150th anniversary and the great step forward it represented in the development of the railways. My dad rendered various services to the venture and received this stick by way of thanks.

The railway’s moving spirit was of course George Stephenson, helped by his equally remarkable son Robert. Meanwhile at the other end of England another pioneer — and a good friend of George’s — was making his own contribution to the railway revolution: Richard Trevithick of Tregajorran in Cornwall, a quite distinct Celtic heartland.

Over a long and peripatetic career, Trevithick designed and built locomotives in his heartland, in Wales, London and indeed South America, with names that resonate down the centuries, especially Puffing Devil and Catch Me Who Can…

Trevithick took on all sorts of challenges, including building the first tunnel under the Thames, a steam tug with a floating crane powered by paddle wheels — and trials of a very different sort: an immensely strong man, Richard was a champion Cornish wrestler.

Perhaps the most extraordinary venture in his career was the decade he spent working on various mining projects in Peru, Colombia and Costa Rica, none of which came to much. Nearly drowning and being eaten by an alligator, Trevithick finally reached Cartagena in Mexico hoping to catch a ship home. There was only one problem: he was skint. Then rather remarkably someone he knew pitched up on the quay one day: Robert Stephenson, returning from his own failed South American venture, last seen by Trevithick when he was a bairn.

Robert gave his father’s pal £50 to get home to Cornwall, where his astonishing life continued a little more sedately, his wondrous walking stick in his massive fist. And how thrilled was my Dad when it passed into his possession, just as pleased as I am to have it and eight other sticks, all with their own distinctive provenance.

However, the crowning irony of this story is that I’ve never actually used any of them, preferring to walk unencumbered.

Mind you, that may change. Past my three score and ten, I may soon need their help. At least I’ll have plenty of choice…

Thanks for a wonderful read! Feels more like a lovely chat by the front door, trying out the walking sticks while sharing glimpses of a life well trod. Insights and memory-prompting.