Update from The QT: The world of Charlie Rogers

In May 2024, Michael Chaplin wrote a piece for The QT on the lost world of the artist Charlie Rogers and his haunting images of Gateshead — the hometown he loved so much

Yesterday’s Eyes & Ears Extra 13.07.25 included the news that an exhibition featuring the work of local artist Charlie Rogers has just opened at Gateshead Central Library.

That is thanks, in no small measure, to Brian Rankin who has devoted much of his life over the last couple of years to Charlie’s work - along with a large part of his art gallery in Low Fell that used to be the family furniture business.

In May last year, award-winning writer Michael Chaplin, a regular contributor to The QT, penned a fascinating essay about Charlie, a man who was friends with Norman Cornish and was on more than nodding terms with LS Lowry.

Here are the words of a master storyteller.

One Monday morning long ago, a young man called Charlie Rogers limped down Bensham Road in Gateshead, wincing as he went. Two days before, this ‘ageing left back’ (his description) was playing in a Cup-tie for Kibblesworth Colliery Welfare when he got ‘a hefty whack on an already dodgy left knee’. The doctor studied it, tut-tutted grumpily, told his patient he should take a week off work and gave him a prescription for a bottle of ‘Fiery Jack Liniment’.

While the young man who once had a trial for Sunderland FC and boxed for the British Army was in that part of town, he called on his elderly aunt, the splendidly named Mrs Violet Gwendoline Woodhead. While sipping his tea, he gazed at the view from her front window. Something struck him about the back lane opposite.

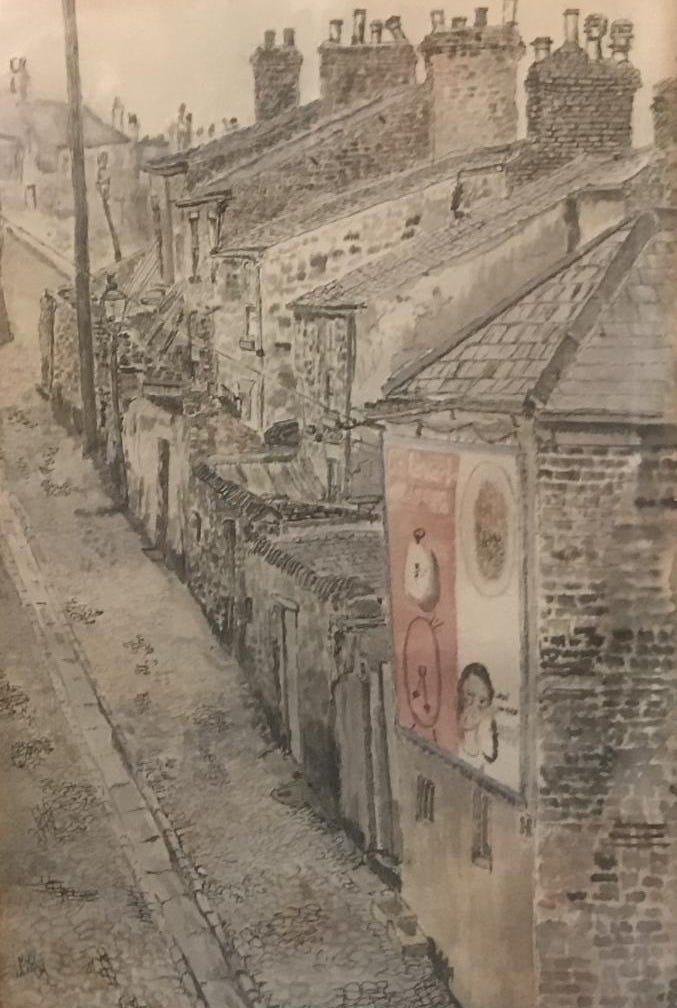

There was nothing special about it — there were hundreds of similar lanes in Gateshead — but in a way that was just the point. This view, with its lines and angles, seemed to represent them all, and with his week off work, the young man decided to paint it. For about 2-3 hours over five or six mornings, Charlie painted the view, trying what he described as a ‘pen and wash’ technique. The result was titled Back Cotfield Street…

He didn’t know it then, but the life of Charles Henry Rogers had just changed. Several other local scenes followed, after which Charlie later declared, ‘I had caught the bug.’ He had found his metier and purpose: to record in his art the life and landscape of his hometown, which he would pursue unerringly for the next 56 years, building up a vast collection of paintings and drawings of buildings, bridges, pubs, lanes, parks and of course the people of Gateshead going about their business.

Down the centuries, around the world, a strong sense of place — often their place — has been crucial to many artists. Think of Claude Monet and his sumptuous garden at Giverny; the Suffolk of John Constable; the little town of Cookham by the Thames, which so fired the extraordinary imagination of Stanley Spencer. Closer to home, there’s the Aspatria of Sheila Fell and the two seaside places of Seaburn and Berwick which so haunted her mentor, Laurence Stephen Lowry, he visited them many times, principally to paint haunting pictures of the sea.

Finally, there’s the Ashington Group, rightly celebrated in Lee Hall’s brilliant play The Pitmen Painters, and their later counterpart in County Durham, Norman Cornish, whose marvellously rich and long career as an artist was built on the rock of his obsession with the people and streets of his hometown of Spennymoor in Co. Durham.

Many years ago, Charlie Rogers joined that great tradition. You may not have heard of him, but my hunch is that you will soon see and hear a lot more about the man, his life and work, and absorption with his special place: Gateshead. In a sense Charlie Rogers is coming home.

Charlie was pleased by that first attempt at picture-making. As he wryly put it: ‘I found it very therapeutic, my knee being cured within the week. I tried one or two more pictures in that part of old Bensham, Finn Street and Gibson Street. Working outside whenever the weather permitted, I tried to capture the character of these odd up-and-down streets with their corner shops, cobbles and ancient green gas-lamps.’

It helped that Charlie found a series of jobs that involved working outside, as a groundsman for Durham County Council, also erecting TV aerials for Rediffusion, though his mate complained Charlie often neglected his role holding the ladder steady and wandered off to draw an image that had caught his eye…

In the mid-60s Charlie took evening classes at Newcastle’s College of Art and Design, so impressing his teacher that he recommended Charlie to the artist Harry Lord, who ran the Univision Gallery in the Bigg Market.

The fledgling artist got lucky: a painter had just dropped out of a three-artist exhibition, so Harry invited Charlie to take the spot — his first show! Others soon followed: another Newcastle gallery run by Scott Dobson (of Larn Yersel Geordie fame) took him on; he had a show at his home-town’s Shipley Art Gallery; he was then invited to show at the Scottish Royal Academy in Edinburgh alongside the eminent landscape painter Sir William McTaggart.

Finally — get this! — Charlie entered work for London’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and ‘amazingly found myself being hung alongside the likes of Edward Ardizzone and Ruskin Spear’, the first of four appearances at one of the biggest shows in Britain’s fine art calendar. This was in 1967 by the way, just three years after Charlie had picked up a brush for the first time, to paint Back Cotfield Street from his Auntie Violet’s front window.

And then?

And then what, you might ask?

Well, just that it seems to me Charlie had made such a splash with his work he might have capitalised by getting on a train to King’s Cross to make a future and maybe his fortune in the great metropolitan art scene of the capital.

But Charlie didn’t do that. I suspect it never even occurred to him to leave Tyneside. He was a Gateshead lad and knew deep down that it offered him all he would ever need as a painter — indeed as a human being. This was doubly true after he met a librarian from Hexham called Ann at the Oxford Galleries dance-hall in Newcastle in 1972. They married the following year — enjoying an unglamorous honeymoon in Dewsbury and Manchester, Charlie producing a visual record of the trip — and their only child Charlie Junior was born the year after. Charlie Senior now had everything he wanted in life.

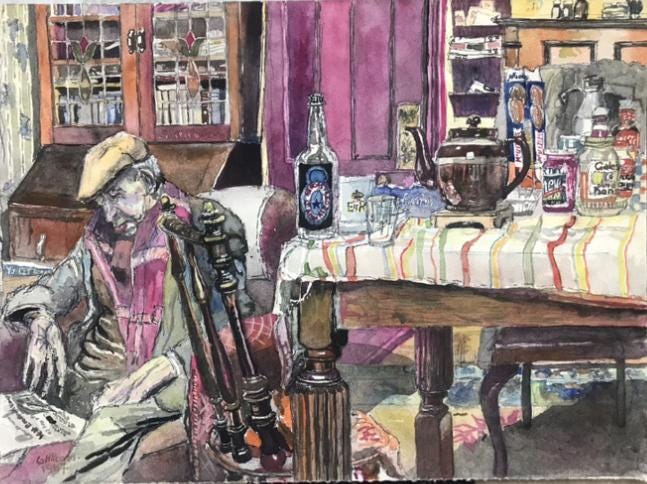

After becoming a full-time artist, Charlie developed an unchanging modus operandi. Day after day, he would leave the family home in Low Fell and roam the streets of his town, closely observing houses, streets, public buildings, pubs, unfolding vistas and of course back lanes, which he once described as ‘pure inspiration’.

He had a special fondness for Saltwell Park, which was on his doorstep. Some paintings included figures, many without, the artist’s imagination capturing anything unusual. Rather than sketching with pencil, Charlie preferred to paint directly onto paper held in place on a board with bulldog clips.

Wherever he went Charlie carried two small palettes in his pocket and indeed he never actually owned an easel. He became a familiar figure around the town; people would stop and talk to him about their lives.

The 1960s and 70s were a time of significant change in the urban landscape of Tyneside, with the collapse of old industries and the flattening rather than the regeneration of Victorian and Edwardian housing. Charlie observed this as it happened, preferably before it happened. He later joked that it felt like he had spent much of his painting career ‘being pursued by bulldozers…’

In addition to reflecting this public world, Charlie also produced a wealth of paintings and drawings of his family life. One of his very first works was a portrait of his sleeping father, who he always called Pop. After Charlie Junior was born, the painter lovingly recorded his passage through boyhood and beyond. Not content with that, he produced literally hundreds of paintings of furniture and fittings in the home.

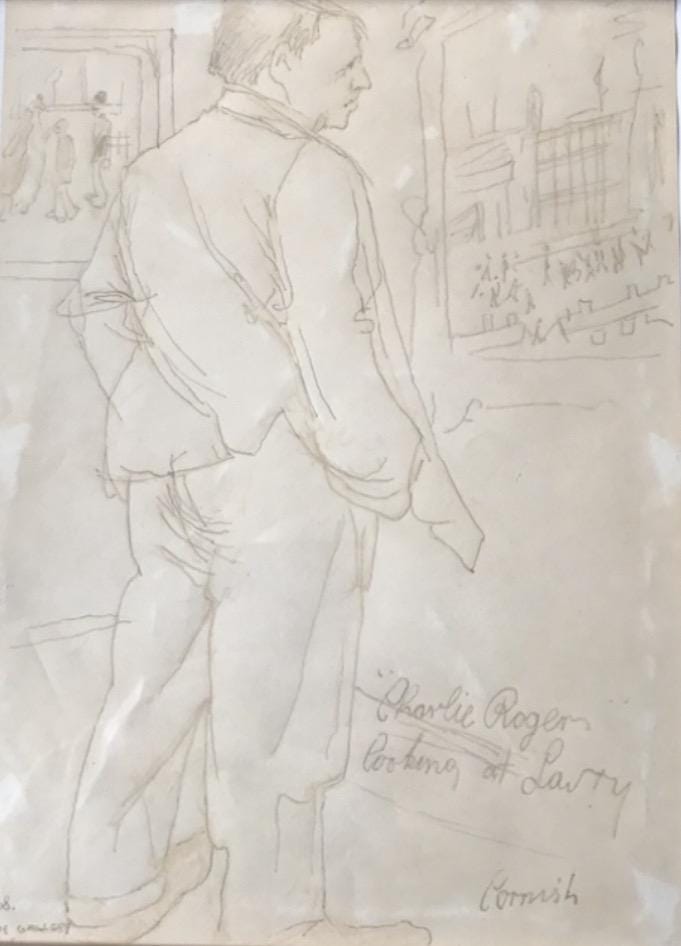

One of the pleasing surprises of researching Charlie’s life and work was discovering his friendship with another brilliant painter of people and place, Norman Cornish of Spennymoor.

Here I should declare an interest: Norman and my writer father Sid were lifelong pals, who together worked underground at Dean & Chapter Colliery in Ferryhill, also attending the Spennymoor Settlement (the so-called ‘pitmen’s university’) to further their artistic ambitions. Marrers in art and marrers in the pit, you might say.

Norman and Charlie had even more in common and an enduring friendship developed. In the 1970s and beyond they would meet regularly on sketching trips around each other’s territory, drawing street scenes and drinkers in pubs.

Norman produced his version of Charlie’s very first painting, that view of Cotfield Street from Auntie Violet’s house; Charlie painted Norman drawing in Spennymoor; Norman sketched Charlie looking at a painting by LS Lowry at the Stone Gallery in Newcastle and together they produced a brilliant drawing of drinkers’ faces in a mirror at the Hillingdon pub in Spennymoor. Marrers in art and marrers in the pub, you might say.

Norman Cornish passed away in 2014, painting to the end, and it was my great privilege to give an oration at his funeral. I think Charlie would have been there, but to my loss we never met.

The following year his beloved Ann died and Charlie dedicated his very last exhibition, at the Low Fell Library in 2016-17, to her memory. In 2019 he was taken into care but continued to paint into his final days. The last of around 1,000 paintings and drawings was of the view from his care home window of roofs overlooking St Vincent Street, near Sunderland Road — in Gateshead of course.

The painting was half-completed when Charlie died at the end of an immensely productive half-century recording his place and its people, all of which, he wryly noted, ‘I owe to that dirty little ginger half-back who temporarily crippled me long, long ago.’

Charlie Rogers is buried, together with Ann, at — where else? — Saltwell Cemetery in Gateshead, his remarkable story ended.

Then again, maybe not…

Enter the Gateshead artist Brian Rankin. Last year as he prepared to open a new gallery, Brian discovered the immense artistic and indeed physical legacy left behind by Charlie and set out on a mission to celebrate and promote it. In this he has been helped greatly by the family of Charlie’s good friend Norman Cornish, who have been down this road themselves in the last 10 years. Brian has curated a brilliant exhibition of Charlie’s work at his Come View My Art Gallery in Sheriffs Highway, Low Fell and been much cheered by the delighted response of people to the story.

‘So many of the visitors here have loved the work and thanked me for giving them the chance to bring younger family members to see their town in the not-too-distant past.’

Brian is also discussing with Gateshead Council the opening of a Charlie Rogers trail around his beloved Saltwell Park and a permanent exhibition in Saltwell Towers, the delightful former home of stained-glass manufacturer William Wailes. As for the town’s Shipley Gallery, it must surely mount a retrospective of Gateshead’s own. I think they would find people queuing around the block to see it, with this art lover at the front.

Many years ago, Charlie Rogers felt compelled to defend his friend in print from the jibes of ‘intellectual’ critics who sneered at his work depicting the lives of the common people:

‘Norman Cornish has stuck down for us that something characteristic of the North East, not only what it looks like, but what it also feels like. For me, it’s taken one hell of a good artist to do that —and this man has done that and this man is one hell of a good artist! Which is why people are drawn back again and again — and always will be drawn back — to his paintings.’

Knowing him as I did, I’m sure Norman Stansfield Cornish would have said just the same of Charles Henry Rogers.

A brilliant artist and a terrific write-up. Such a shame he hit intellectual snobbery, especially when one of the first paintings shown here looks so very like the work of John Bratby, who became an RA. But then he was born in Wimbledon. We still have a north/south divide. 😡